By the time I was 10, I knew the year and model of every Ford, Chevy and Mopar on the road, and could not wait until the day I could drive. Seeing this, Daddy decided to give me some driving lessons, which he did without even cranking up the car.

Our classroom was a 1951 Plymouth, baby blue with a fastback, sitting in the driveway of our little shotgun house. Of the then-premium appointments — AM radio, heater and white wall tires — it had only a heater, probably because you couldn’t buy a used car without one.

“You don’t need a radio in your automobile, son,” he said. “No, sir. A radio will just take your mind off your driving. And you have to keep your eye on the other fellow.

“What you need is good tires. Not whitewall tires. They don’t hold you up a bit better just because they got a white stripe on them. You just need good black walls, with good tubes…”

He held up his thumb and index finger pinched at an eighth of an inch. “…. And at least this much tread. Your tires are what hold you up.”

“What do you think’s most likely to mess up a tire?” he asked.

“You run over a nail?”

“Yes,” he said. “Which tire will pick up a nail first?”

I shrugged my shoulders.

He pulled out a nail with a head on it, and laid it flat on the ground. “How in the world would this puncture your tire?”

“I didn’t know, Daddy.”

He knelt down, making a motor sound with his lips, as he “drove” over the nail, and left it standing straight up.

“The front wheel hits the nail and makes it stand up?” I asked. “Then the back wheel runs over it?”

“Exactly,” he said, as he hugged me again. “Let’s take a tire off.”

We pulled the full-sized spare out of the trunk, along with a bumper jack, its base, and its handle, which doubled as a lug wrench.

“A flat tire scares a new driver more than anything else,” Daddy said. “Because they’re afraid they won’t be able to change it. So let’s play like you’ve had a flat, and you have to take the tire off.”

I wasn’t really sure what to do. I had seen Daddy take a tire off the rim, take the inner tube out and patch it, but I never paid much attention to how he got the tire off the car. But I knew that to get at the lug nuts, you had to take the hubcap off.

He handed me the lug wrench, and I put the wedge-shaped end up against the crack where the cap met the rim.

“Push it in and twist it,” he said.

I twisted, but the cap didn’t pop off until Daddy showed how to knock it into the crack with the heel of my hand. When it came off it rolled around, then fell upside down in the dirt.

“What are you gonna do now?” he asked.

“Take the bolts off?” I said.

“Just loosen one first.”

I put the lug wrench on the top nut, with its handle pointed at two o’clock. When I tried to turn the wrench, the lug nut wouldn’t budge.

“What are you gonna do now?” he asked me.

“Hit it with a hammer?”

“Have you got one?”

“No, sir, but there’s one in the house.”

“If you were out on the highway with a flat tire, would you have a hammer?”

“No, sir.”

“So what are you going to do?”

“I don’t know, Daddy. This is hard. I can’t do this.”

“Don’t say can’t, son; that means you’ve quit. If you’re out on the highway you can’t quit.”

I just looked down at the ground.

“Make a fist. Make it look like a hammer.”

I made a fist and held it up when I bent my wrist. I looked at Daddy. “Like this?”

“Now you’re getting it.” he said. “ What’s like your hand and arm, but stronger?”

“My foot and my leg!” I smiled. “I could stomp it.”

“Atta boy!” he smiled, clapping his hands. “Try it.”

I reset the lug wrench at about three o’clock, stood on one foot and stomped it, but the lug wrench never moved.

“Could I stand on it, Daddy?” I asked.

“Absolutely.” He came up and put his arm around me. “Now loosen that lug.”

He helped me climb up on the lug wrench handle, where I held on to the side of the Plymouth, and boogied my body. After a few boogies, the lug wrench moved …a little. I reset the lug wrench to three o’clock, climbed on it and boogied again. That time it moved a lot.

Daddy laughed. I did too. Then, with both feet on the ground, I turned the wrench ‘til the bolt fell out.

Daddy pointed to the hub cap, lying on the ground.

I picked it up, laid it next to the wheel, and then laid the lug nut in it.

“Good job,” Daddy said. “Now put the nut back in with your fingers and tighten it. Then lug wrench it back as tight as you can get it.”

I did that, then I set the wrench at three o’clock, climbed on it and boogied the nut tight with my body.

Daddy nodded his approval. “Let’s road test that tire, son,” he said, putting his arm around me again.

“It’s hot and we need a Co-Coler,” he said as we got in the car. He knew full well that he would pull a six-ounce Coke out of John MacRae’s water-cooled drink box, and that I would pull a 12-ounce Pee Dee Club.

A little more than six years later, Daddy finished these driving lessons as I drove the back roads around the prison camp.

I was 29 years old when I lost him in December 1971. But it was only today that I realized how much those driving lessons have meant to me. About so much more than driving: taught by the Socratic method, they had taught learning by doing; sticking with the job, and figuring out things for yourself; making do what you have, and — perhaps most importantly — about being a good father.

I am so thankful for what my Daddy taught me… and how he went about it. You were a good father. I’ll be thinking about you on Father’s Day.

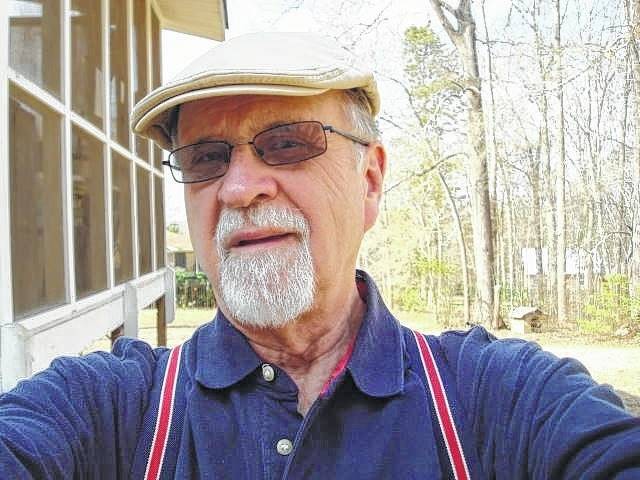

Leon Smith, a resident of Wingate who grew up in Polkton, believes the truth in stories and that his native Anson County is very near the center of the universe.