Author’s note: The memories of Joyce Driggers Hardaway, Tim and Sylvia Knotts, and Elaine Gardner were among those used in writing this story.

An evening mist was falling on Wadesboro when I left the church. So I hurried to my Beetle to find a folded half-sheet of notebook paper on its windshield. I opened it to read the words: “Dear Leon: I am lost. Don’t talk to me about it. Just pray; Robert Driggers. ”

The note confused me. Robert played piano at the church, hymns of such grace and deep feeling, that he had to believe the songs he played. Robert never missed a Sunday or Wednesday at the piano, but he did slip into place behind the half-wall, undetected, then maintain his anonymity by bending so low over the keys that he could kiss them. At the end of the services he remained an invisible man who did not believe the hymns he played.

My curiosity was piqued, but all I could do was respect his request. I was just filling in at Cathedral Baptist Church, so I could only hope that Robert would talk to me in the two weeks before the new pastor came. Although Robert and I saw one another in the back hallway before each service, he simply said, “Hi,” and walked into the sanctuary. On March 9, 1986 I finished my work there, without any word from Robert.

He grew up attending Bethany Free Will Baptist, going there every Sunday with his mother and his seven siblings. It was there he heard the hymns he taught himself on his mother’s piano.

But he reached the age of accountability, which we thought was 12 years old, without the Lord having called him. He finished his education and married Joyce, who he met at Bethany, without any call. He went to work and moved up in West Knitting Mill, becoming supervisor of the sewing room. Still no word.

He did not hear from the Lord in Vietnam, where he joined an Army search and rescue unit in 1963, nor back home in 1969 when he and Joyce invited four year-old Lynn and two-year old Jodie to become their daughters. Joyce took the girls to Bethany, and prayed for her husband, while Robert took himself wherever he could play church music, and get into the zone. This ability led him to Cathedral, where he played each Sunday morning, Sunday night and Wednesday night. On Tuesday nights he visited Tim and Sylvia Knotts to work out songs for the choir and to talk.

The round-the-table discussions often centered on why Robert would not become a Christian. These pointed talks did not dissuade Robert. Maybe he was disappointed that he saw too many Christians who made promises they did not keep, and who became slippery at tax time, when they under-reported their income to the IRS. Or maybe it was because Robert knew quite well that one must be called to become a Christian. You could not just join up; you had to hear from the Lord. And he had not. And until he did, he would just be a heathen. And though his wife, his daughters, and his many friends kept praying for him, it looked like he might just stay that way.

But the Sunday before Easter 1986, the church, just across US. Highway 74 from Bethany, learned they would have to replace the speaker for their revival meeting, which would begin on Monday and run through Friday night. Having exhausted every other possibility, Wade Baptist turned to me. I said I would do the best I could. I would need a lot of help.

I hoped Robert might come to the meeting, but the first three nights passed without him. But, at the end of the service on Thursday night, I spotted him, hunkered down in the next-to-last pew along the right aisle. I looked at him, but he did not return my glance. I started to close the meeting when I heard a voice.

“Go get Robert,” it said.

“Lord, you know I don’t do things like that,” I answered, squirming. “Robert asked me not to bother him. You know how he is. I just can’t do that.”

“Go get Robert,” the voice called again.

I was afraid to go… but more afraid not to. So I drew in my breath, stepped to my right, and headed toward Robert’s pew. I neither knew what I would do, nor what I would say. But when I reached him, in my own voice I heard, “Robert, is it time?”

Robert did not answer right away. But then he looked at me and said, “Yeah,” then got up and followed me to the front. Seeing us, the pianist stopped playing and the choir stopped singing. When we got to the altar table and faced the congregation, I asked Robert what had happened. He told us he was answering a call to become a Christian.

The entire house began to clap and shout, as his many friends celebrated Robert’s joy.

Robert did not say another word. He waited for that until he got home. When he came into the house, Joyce saw something different about him.

“What is it, Robert?” she asked.

“I got changed tonight.”

“You got saved.”

“Yeah.”

“I am so proud of you,” she said. It was March 28, 1986. Robert Driggers was 43 years, six months and 12 days old.

Perhaps a month later, I got a small envelope in the mail. In a hand like the one in the VW note, I read, “Dear Leon: I am the happiest I have ever been in my entire life; Robert.”

I did not see Robert until that fall, when I heard a piano playing inside another church. Its power and grace sounded a lot like Robert. But the music was happier somehow, and at the piano I saw him sitting straight and tall. I would not see him again.

On Christmas Eve, 1986, Robert worked at West Knitting Mill ‘til noon. He had already bought and wrapped the presents for his family, but he had a few things left to do. He picked up Jodie to drive her to her Christmas break job. Riding in his rust-colored Datsun, they talked about Christmas, then promised each other to give up smoking. It was the right thing to do, he said; maybe it would stop his headaches. They said goodbye as she got out at Kentucky Fried Chicken, and turned east onto Highway 74, driving to the company office to ask about his sister’s paycheck.

Witnesses saw him slumping over the wheel of his Datsun as it crossed into the westbound lane and collided head-on with a pickup truck. The driver of the pickup survived the crash, but Robert did not. Witnesses believed he was dead before the steering column severed his aorta.

On Christmas Day, his daughters, 19 and 21, asked their mom what should they do about their daddy’s Christmas gifts. Joyce said Robert would want them to open their presents. They did. Joyce did too, to find a pair of bedroom shoes, a pair —yet not a pair— because the box held one single shoe.

They saw the irony in the gift; yet bereft on Christmas day, they praised God for Robert Driggers’ Joy.

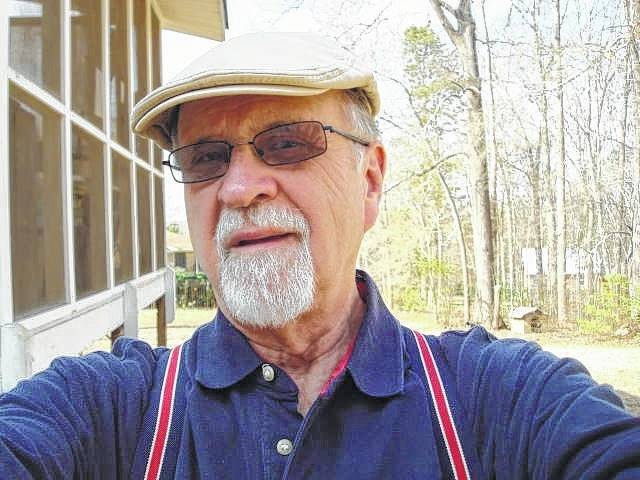

Leon Smith, a resident of Wingate who grew up in Polkton, believes the truth in stories and that his native Anson County is very near the center of the universe.