On the way home from Uncle Lon’s, I thought about the black Model A Ford we left parked under his barn. Because Daddy didn’t have the money to pay for her, he had to wait for some good fortune to bring us the $60 we needed.

Actually, it was not good fortune, but an accident, that brought the needed funds. It happened one Friday night when Daddy bumped the power pole beside Herbert Griffin’s Store. But when he came home, he was not sad, but was grinning.

“That little old dent don’t hurt a thing,” he told me. “We’re gon’ to turn it into a Model A Ford.”

So when the check came from Nationwide, we drove downtown to cash it, pick up 20 feet of rope, and head across Brown Creek. There was no way for us to call ahead. Uncle Lon was always home, but he had no telephone, and neither did we. But he came out the minute we pulled up, and walked with us down to the barn.

“There she is, backside to the weather, just like we left her,” he said. “Key’s still in the switch.”

Daddy handed me the envelope to count out the six $10 bills into Uncle Lon’s hand.

“Thank you,” he said, as he stuffed the bills into the chest pocket of his overalls.

“Can we crank it up?” I asked.

“We’ll try to push her off, we get up to the yard,” Daddy said.

So we walked under the shelter, where Daddy stood at the driver’s side door, and Uncle Lon and I took the front fenders.

“Son,” Daddy said, “you can push harder, if you push backwards.”

So I turned around, and we all pushed until we got her backed out and pushed up to the broom-swept yard near the house.

Daddy climbed in, put her in low gear and pulled up the emergency brake. Uncle Lon came over.

“Don’t trust your foot brakes, “Uncle Lon said, “Yank up the emergency brake if you want to stop in a hurry.”

Daddy took the gas cap off the tank, which served as a firewall, and pushed on its side. A little gas sloshed in the tank. Daddy opened the petcock that let it flow to the carburetor. We checked the oil, and got some water at the windlass.

“Turn the key on,” he smiled. “Don’t you drive off and leave us if she cranks.”

So he and Uncle Lon got behind me and pushed me off.

“Now,” he said reaching a fast walk.

I dropped the clutch, but the old motor only went “choo choo choo choo. “

We tried again with the same result.

“Battery might be too dead,” Uncle Lon said.

“Can we try just one more time?” I pleaded.

Daddy shook his head. “We better get on home,” he said. “We only got about a half-hour of daylight left.” So we tied the rope from the back of the Plymouth to the frame of the Model A, and I climbed in.

Uncle Lon came up and patted her on the hood, then looked at me. “You take good care of my old car,” he said.

“I will, Uncle Lon,” I answered. “Thank you for selling her to us.”

Daddy came over. “We won’t go fast,” he said. “But watch my taillights and put on brakes when you see them light up.”

So he climbed into the Plymouth, cranked up, and we waved goodbye to Uncle Lon. After Daddy took up the slack in the rope, I let off the emergency brake and we started our journey home. I looked back to see Uncle Lon watching us take his car away. I felt sorry for him.

“Clunk,” the Model A ouched as her bumper hit the Plymouth’s. Daddy had stopped at the end of the long drive way.

He got out and came back.

“You got to use your head, Son,” he said. “Keep your eyes on my taillights.”

“I’m sorry, Daddy,” I answered.

He checked the knots in the rope, headed for his car, then stopped and came back.

“We can try to crank that thing before we get to 74,” he said. ”Turn the key on, put her in second and hold in the clutch. When I get up some speed on the hard surface, I’ll blow the horn, and you let off the clutch.”

We must have been running about 20 miles per hour, when he blew the horn. I dropped the clutch, but the motor said only “choo choo choo choo.” So I pushed the clutch back in.

We tried to crank her one more time before we got to the prison camp, but she would not fire. There we stopped before making the left turn that ran down the long hill to 74. Daddy got out, checked the knots again, then came over to me.

“Don’t try to crank her again until we cross Brown Creek Bridge,” he said. “That will be our last chance.”

Going down the long hill, I noticed the speedometer was not working. After we crossed Brown Creek Bridge, I dropped the clutch again, to finally realize that my old car’s motor was not working either.

So, I put the shift in neutral and coasted. Daddy bore right toward Polkton, slowed down where the road made a “T” at the bus station, then he turned up toward the Depot. Watching Bennie grinning from the white store, I had to skid the tires to keep from running into Daddy again when he stopped before turning left onto 218.

He turned right at the top of the hill and drove ‘til the asphalt ran out, then turned into the dirt path, about a tenth of a mile above our house.

“I’m sorry she didn’t crank,” Daddy said as he came up. “When warm weather comes, I’m gon’ talk to Jim Allen. He’ll make her run like a sewing machine.” Then he walked to the rear of the Plymouth and began untying the rope.

I put the Model A into reverse, set the emergency brake, then got out to untie my end.

Daddy carried the rope to the car, cranked up, then turned around near the tree house, and stopped for me to get in.

“I want to stay up here for a little while, Daddy,” I said.

He nodded and headed home. I watched as he drove onto the black top and out of sight .

Then I climbed in the A-model to look her over. “You need a name,” I said after a while. “What could I name you? “

Just then I remembered an evening, seven years before, when Mr. Roberdel Smith drove up to our little house with old fat, lost Major riding shotgun. He turned off the black ‘31 Chevy coupe and got out.

“Me and Old Potchie done brought your blankety-blank old fice dog home,” he smiled.

The vision ended. “Old Potchie,” I said. “Old Potchie. That’s it.”

I patted my little ‘31 Ford on her dash. “I‘m gon’ name you after Mr. Roberdel’s car, even if she is a Chevrolet,” I said.

It was just about too dark to see when I got out, patted her on the gas tank, and called her name for the first time.

“Little Potchie,” I smiled. “I never even heard you run, but I already think a whole lot of you.”

I patted her again, then turned and walked toward the gleam from the windows of our old frame house. Then I stopped and looked back.

“I’ll be back to see you tomorrow,” I said, then walked down the long path, home.

Next time: Hearing Potchie run.

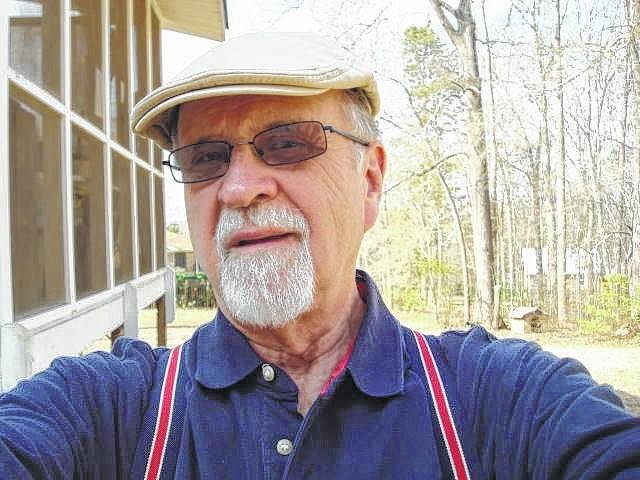

Leon Smith, a resident of Wingate who grew up in Polkton, believes the truth in stories and that his native Anson County is very near the center of the universe.